Share this

Flexo Chronicles: Anthology of Flexo Printing | Part 1 of 2

by Luminite on Jul 20, 2022 9:42:31 AM

Flexographic printing has exploded in popularity over the past two decades, with roughly 60% of the entire packaging industry utilizing flexography in the construction of their packaging.

Modern-day flexography has come a long way since its invention some 130 years ago. From the invention of the first rotary press using rubber plates to print to the commercialization of UV pigments in the 1990s, this two-part series covers the origins of Flexo printing as well as its growth in popularity through the present day.

Part One: The Inception of Flexographic Printing through the 1950s, will cover flexographic printing from its conception through the 1950s. Part Two: Flexography Through the Modern World covers new products and applications developed from the 1960s through current-day flexo operations, including the impact that the Flexographic Technical Association (FTA) had on the flexo industry.

Flexo Chronicles: A History of Flexography | Part 1: Inception of Flexographic Printing Through the 1950s

Conception (1853) through the 1920s:

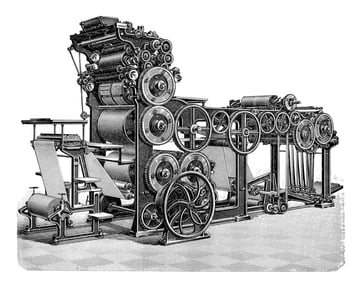

The first adaptation of flexographic printing can be seen some 170 years ago when an English paper bag printing company, Bibby, Baron, and Sons, developed a unique rotary press that used rubber plates and a homemade ink consisting of dyes and sugar that was dissolved in water.

Though the first attempt was largely unsuccessful, the idea of a rotary press using rubber plates grew and technical design improvements were made. These rotary presses began to grow more efficiently.

Though the first attempt was largely unsuccessful, the idea of a rotary press using rubber plates grew and technical design improvements were made. These rotary presses began to grow more efficiently.

Around the same time that Bibby, Baron, and Sons were developing their rotary press, Charles Holweg, a French businessman, and his brother August decided to enter the soaring paper bag trade by opening a manufacturing plant for this crucial packaging option. With the growing demand for individually wrapped products, a more efficient printing process was needed.

In 1903, Charles Holweg learned of this new rotary style press and decided to develop a press that utilized a synthetic aniline dye ink compound due to its fast-drying nature. Since Charles knew these inks dried so quickly, he attached the press to one of his bag-forming machines, thus creating the first example of continuous print operations for packaging.

Throughout the early 1900s, multiple advancements were made not just in the printing industry, but also in the packaging industry, with corrugated cardboard becoming an ever-popular packaging option. In 1914, the Interstate Commerce Commission approved the use of corrugated cardboard as an official packaging material because of its protective nature and capabilities that were similar to wood.

With tensions rising and World War I approaching on the horizon, the shift in demand from wood to corrugated was welcomed by most due to the low supply of wood packaging caused by the world war. But this shift in demand also created new challenges, and box manufacturers needed better printing solutions to meet the increased product demand.

Since the presses were very simple in design and to save time and capital, a large number of corrugated box manufacturers decided to build their presses, formulate and prepare their inks, and even created the rubber plates needed for printing. Most examples of these early presses failed due to incorrect ink formulas and the general lack of ink-metering.

Withstanding the growing popularity of corrugated material, there were also new paper materials being introduced nearly every day. These paper packaging materials featured waterproof, greaseproof, or alkali-proof properties, making it easier to package more sensitive products like soap or meat.

As the 1920s came to a close, the world was demanding individually wrapped products and the packaging market exploded. Manufacturers and printers both scrambled to improve their press designs, ink formulae, and printing processes to keep up with the demand.

Printing through the 1920s and 30s

With the increased demand for product packaging, press operators and packaging manufacturers were faced with the growing challenge of creating the perfect ink, and most ink-makers disregarded aniline printing entirely due to its poor quality. It was not until 1927 that the first ink using tri-methyl methane dyestuff that was dissolved in cellosolve and chemically fixed was created. This ink prevented bleeding when wet. Soon after its invention, the first dry inks were created by companies like National Aniline, Calco Chemical Co., and DuPont.

These new “dry” inks were extremely desirable because they featured:

- Long shelf lives

- High-melting points

- Solubility in alcohol

- Fast-solvent release

- Good-color properties

- Compatibility with aniline dyes

While ink chemistry was advancing at a fast rate, with some of the acidic chemicals used being extremely toxic, ink manufacturers had to be cautious about the chemicals they were using in the manufacturing process. Not only could they be harmful to anyone exposed to them, but certain chemicals caused the rubber plates to harden and crack, becoming unusable in the printing process.

Throughout the Roaring Twenties, the standard of living in the United States was growing, and consumers now demanded well-designed, good-looking, yet disposable packaging. However, even with the advancements in ink, it was not until 1931 that the first pigmented white aniline ink was created using titanium dioxide. To be used as a base coat or as an additive, this pigmented ink gave printers the ability to create opaque colors that were in high demand.

Shortly after the invention of the first white ink, pigmented yellow and orange inks were introduced into the market, followed closely by metallic inks and specialized water-based inks used for printing on paper and cardboard.

While press improvements were happening in the background, the first real innovation to the modern presses happened in 1932 when synthetic rubber was introduced into the plate-making process. The synthetic rubber used to make these plates held up better to the harsh chemicals, didn’t swell, nor did they absorb oil-based inks.

Innovations in the printing industry were slim throughout the Great Depression. However, one inventor, Stan Avery, developed the first self-adhesive paper sheets, giving way to an entirely new industry for flexography to capitalize on.

Aniline Press Evolution of the 1940s and ’50s

By 1940, self-adhesive tape was a booming market and 3M had already released their still-popular-today self-wound tape. Seeing a need for smaller-width printing jobs, Mark Andrews, an established flexographic printer, introduced the first tape printers, or the first iteration of a narrow-web printing press. His company, the Mark Andy Company, was capable of printing very simple one to two-color designs on small (one to four-inch-wide) strips of a substrate.

Nearing the end of the great depression, the Kidder Press introduced a newly designed press for printing on film, where the web travels overhead versus beneath the floor. These aniline printing presses are considered to be some of the earliest ancestors of modern-day flexographic printing presses.

Shortly after Kidder press co-introduced their new press design, they also introduced the first aniline press with a drying system included. The press included hot-air dryers between each printing station for between-color drying. These presses also included vents and exhaust systems that permitted the use of higher-pigmented inks.

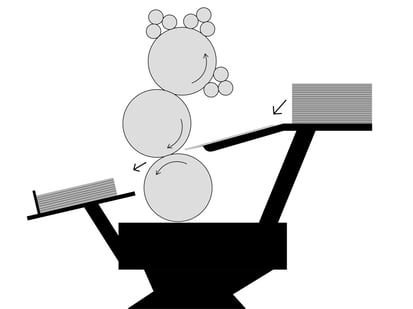

One of the most important developments in the history of flexography happened In 1941 when the Interchemical Corporation introduced the first mechanically engraved metering roll, referred to as the anilox. The anilox roll was created to help meter and control the thickness of the ink that was being transferred from the plate to the substrate.

Another important update to the aniline industry happened in the late 1940s when the Mosstype Corporation launched the “Mounter-Proofer” - a machine that was used to address the issue of registration. The “Mounter-Proofer” provided an easier way of getting the cylinders ready while they were still off of the press. If the plates were made incorrectly, they would never register and would never be mounted on the press.

By the 1950s, flexography was being used to print many different kinds of packaging including:

- Grocery bags

- Counter rolls

- Wrappers

- Tapes

- Tubes

- Laundry soap boxes

- Ink bottle caps

- Corrugated paper

During these years an increase in newly designed narrow-web presses was introduced to supply a growing market for pressure-sensitive labels; while at the same time, extremely large (wide-web) presses were also being designed to satisfy the need for printing on corrugated boxes.

Throughout the late 1940s, most press houses were printing-packaging used by the food industry. But the name “aniline” started to become a problem because aniline was generally accepted as a highly toxic and harmful substance.

To sell their products, the aniline printing industry started to advertise their process with terms such as “Lustro printing” or “Transglo printing.” In March 1951, Franklin Moss, president of Mosstype Corporation, decided to write in the Mosstyper, a publication produced by his company, to suggest new names for the process.

He enclosed a postcard with every copy so readers could submit their suggested names. Eventually, Franklin Moss received more than 200 name suggestions. The long list was narrowed down to three names: flexography, rotopake, and permatone.

A ballot campaign was included in various printing-industry magazines, including the Mosstyper so that readers could choose a name from the three finalists.

On October 22, 1952, at the 14th Packaging Institute Forum in New York City, flexography was announced as the new name. The term flexography and the adjective flexographic were adopted very quickly and gained worldwide acceptance.

As interest in flexography grew throughout multiple industries, the first flexographic forum was held in 1957. Due to the success of this forum, the Flexographic Technical Association (FTA) was born the following year. The association was charged with making "all existent knowledge available as well as to encourage and promote new technology."

The first technological forum was held in New York in February 1959, and the first edition of the book Flexography Principles and Practices was published in 1962.

Up through 1960 flexography experienced an incredible rate of development. Presses ranging from one-inch widths for cellophane tape up to nine feet for preprinting on corrugated packaging were produced and new substrates were introduced daily.

But these presses weren’t perfect, and the latter portion of the century brought innovative new designs and products to supplement the newly-rebranded Flexographic printing industry.

The Luminite Impact:

Luminite Products Corporation was founded in 1926 in Salamanca, NY, and was formed to supplement the acquisition of a newly invented aluminum alloy – called Luminite – which, unlike pure aluminum, was easily machinable.

These cylindrical aluminum bases were cast and machined in Luminite’s foundry and machine shop. This material, together with engraving machines designed and built by the Company, enabled Luminite to provide relief-engraved printing cylinders that were new to the printing market. The principal users of this product were wallcoverings, draperies, and gift wrap manufacturers.

Luminite was the nation’s first full-scale manufacturer of mechanically engraved aluminum printing cylinders.

During World War II, Luminite supported the war effort by manufacturing aluminum and brass parts for fighter planes, machine guns, and tanks. After the war, under the leadership of John F. Vosburg Sr., Luminite expanded the fields of its mechanically engraved aluminum print cylinders with much larger diameter rolls for scenic wallpaper murals, draperies, and other decorative fabrics.

Interested in learning more about Luminite’s capabilities or services? Schedule a print consultation below to speak with a member of our talented sales team today:

Share this

- Flexographic Printing (81)

- Image Carrier (28)

- Elastomer sleeves (27)

- Ink Transfer (25)

- Quality (22)

- Flexo sleeve (20)

- News (18)

- printing defects (18)

- flexo printing defects (17)

- sustainability (13)

- Flexo Troubleshooting (12)

- Ink (12)

- Digital Printing (10)

- Flexo 101 (10)

- Flexo Inks, (9)

- Anilox (7)

- Blister Packaging (7)

- Cost (6)

- print misregistration (6)

- regulations (6)

- Corrugated Printing (4)

- pinholing (4)

- "Tradeshow (3)

- Digital Flexo (3)

- Gravure Printing (3)

- Insider (3)

- Load-N-Lok (3)

- Wide Web (3)

- direct laser engraving (3)

- flexo-equipment-accessories (3)

- gear marks (3)

- halo (3)

- testing (3)

- Narrow Web (2)

- bridging (2)

- feathering (2)

- filling in (2)

- mottled image (2)

- pressure (2)

- Labelexpo (1)

- dirty prints (1)

- doughnuts (1)

- embossing (1)

- kiss impression (1)

- October 2023 (2)

- September 2023 (1)

- August 2023 (1)

- July 2023 (3)

- June 2023 (1)

- May 2023 (5)

- April 2023 (1)

- March 2023 (2)

- February 2023 (1)

- January 2023 (3)

- December 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (3)

- September 2022 (2)

- August 2022 (2)

- July 2022 (3)

- May 2022 (1)

- April 2022 (4)

- March 2022 (2)

- February 2022 (5)

- January 2022 (7)

- December 2021 (1)

- November 2021 (3)

- October 2021 (2)

- September 2021 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- July 2021 (3)

- June 2021 (1)

- May 2021 (4)

- April 2021 (4)

- March 2021 (4)

- February 2021 (2)

- December 2020 (1)

- November 2020 (1)

- October 2020 (2)

- September 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (3)

- July 2020 (2)

- June 2020 (3)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (1)

- November 2019 (3)

- October 2019 (1)

- August 2019 (1)

- July 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (1)

- March 2019 (1)

- January 2019 (1)

- October 2018 (2)

- August 2018 (1)

- July 2018 (1)

- June 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (2)

- October 2017 (1)

- September 2017 (2)

- January 2016 (1)

- February 2015 (1)

- January 2015 (1)

- December 2014 (2)

- September 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (3)

- October 2013 (1)

- September 2013 (1)

- June 2013 (1)

- January 2013 (1)

No Comments Yet

Let us know what you think